INTRODUCTION

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep disorder marked by symptoms such as snoring, repeated breathing pauses, and disrupted sleep, often leading to daytime sleepiness. Left untreated, OSA can seriously degrade an individual’s quality of life, contribute to psychological issues, increase insulin resistance, and elevate the risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality.1–4 Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy stands as the primary and most effective treatment, known to reduce breathing disturbances, daytime sleepiness, and improve overall sleep quality, life quality, and manage blood pressure.5,6 For patients who struggle with CPAP, or find it unsuitable, alternative treatments like oral appliances (OA) and upper airway surgery are available. However, treatment adherence is crucial for the best outcomes, and it’s often a challenge, especially with CPAP.7

Sleep is frequently a shared experience, particularly for couples.8 Given that OSA’s main symptoms—snoring and apneas—occur during sleep, partners are highly likely to experience disrupted sleep. This disruption can lead to daytime impairments and relationship challenges, highlighting the significant impact On Partners. Conversely, effective OSA treatment can also bring benefits to partners by alleviating snoring, apneas, and daytime sleepiness in the affected individual. The dynamics of partner interaction during OSA treatment initiation are varied and can significantly influence the patient’s long-term treatment adherence. This review aims to explore the existing research on three key areas: (1) how OSA affects sleep and daytime functioning as reported by partners, (2) the effects of OSA treatments on partners‘ sleep and daytime functioning, and (3) the role of partner involvement in OSA treatment processes.

METHODS

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases to identify English-language studies. The search focused on the effects of OSA and its treatments on partners’ sleep and daytime functioning, as well as partner involvement in OSA treatments. Reference lists from identified articles were also reviewed. Keywords used in the search included “sleep apnea,” “sleep-disordered breathing,” “spouse,” “partner,” “wives,” “positive airway pressure,” “oral appliance,” and “surgery,” in various combinations. Studies were selected based on criteria including: (1) original study data (excluding reviews or case reports), (2) objective OSA documentation (polysomnography (PSG) in lab or at home) and/or ongoing OSA treatment, and (3) data on (a) sleep and/or daytime functioning (mood, sleepiness, cognitive function, quality of life, work performance, relationship quality) in partners of patients with untreated OSA; (b) sleep and/or daytime functioning in partners of OSA patients undergoing treatment (CPAP, OA, or surgery); and/or (c) the association between partners and OSA treatment use. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included to provide a broad understanding of experiences and concerns related to OSA and its treatment from both patient and partner perspectives. Studies were excluded if partner outcomes were reported by the patient, rather than directly assessed from the partner. A total of 38 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review.

REVIEW OF FINDINGS

Negative Impacts of Untreated OSA on Partners’ Well-being

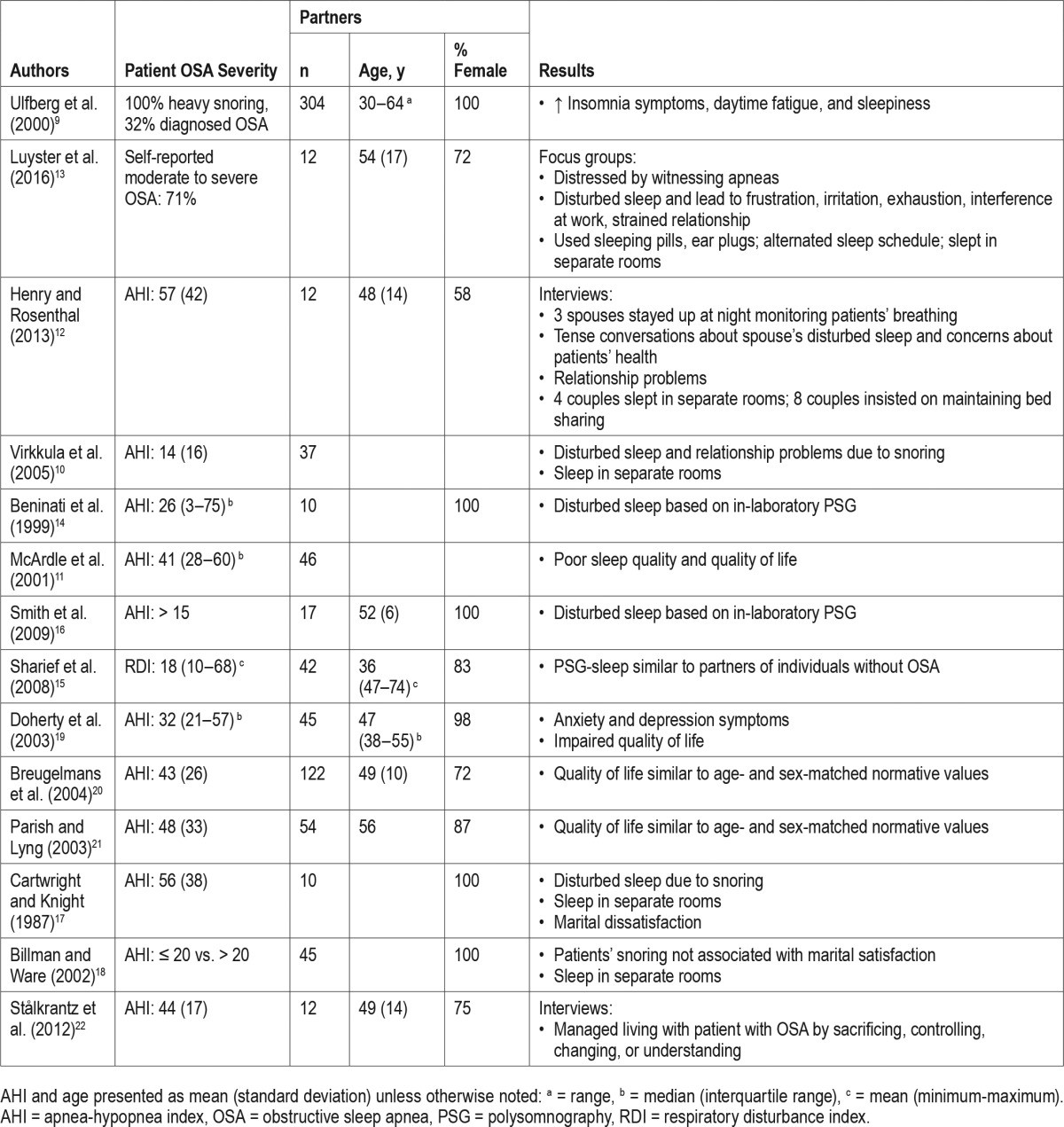

Research consistently shows that untreated OSA has detrimental effects on partners, impacting both their nighttime sleep and daytime functions (Table 1). Compared to partners of healthy individuals, partners of those with heavy snoring and OSA are significantly more likely—three times more likely—to report insomnia symptoms such as difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, and experiencing unrefreshing sleep. They are also twice as likely to report fatigue and daytime sleepiness. These findings remain significant even after accounting for factors like age, BMI, number of children, work hours, the partner’s own snoring, and sleep medication use.9 OSA symptoms are major sleep disruptors for partners. In a study of 37 partners of individuals suspected of OSA, over half (55%) reported nightly sleep disturbances due to the patient’s snoring.10 Baseline assessments from 46 partners in a CPAP vs. placebo trial revealed that a large proportion experienced moderate to severe sleep disturbance from snoring (69%), apneas (54%), and restlessness (55%). Additionally, 66% were classified as “poor” sleepers based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.11 Qualitative data further highlight partners’ distress, with many feeling anxious from witnessing apneas and compelled to monitor the patient’s breathing throughout the night to ensure their safety.12,13

Table 1. Effect of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Partner-Assessed Outcomes.

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t01.jpg

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t01.jpg

Studies using PSG to objectively measure sleep in partners of untreated OSA patients have also documented significant sleep disturbances.14–16 An early study using concurrent PSG on 10 wives sleeping in the same bed as their husbands undergoing OSA assessment found that wives had a median sleep efficiency of just 74% and an arousal index of 21. Up to 32% of wives experienced arousals within seconds of their partner’s snore.14 A case-control study of 17 wives of men with untreated OSA showed increased wakefulness after sleep onset, a higher percentage of stage 1 sleep, and specific brainwave activity disruptions during slow-wave sleep compared to wives of healthy sleepers, even after adjusting for age and menopausal status.16 However, a community-based study involving 110 couples using in-home PSG, categorized by OSA status, found no significant differences in sleep architecture, sleep onset latency, total sleep time, or sleep efficiency between partners of OSA patients and partners of non-OSA individuals.15 This contrasting finding may be due to the community sample consisting of individuals not actively seeking treatment and with milder OSA.

Partners develop various coping mechanisms to mitigate sleep disruption caused by OSA symptoms. These include using earplugs, sleeping medication, and adjusting sleep schedules.10,13 For some couples, snoring leads to separate sleeping arrangements.12,13,17 Others maintain bed-sharing despite sleep disturbances to avoid social stigma and preserve a sense of a “normal” relationship.12 Partners’ sleep loss often results in frustration, exhaustion, work interference, and strained relationships.13 Early research indicated marital dissatisfaction, particularly conflicts over child-rearing, among wives of OSA patients.17 Virkkula et al. found that 35% of partners reported relationship problems due to snoring.10 While husbands’ snoring wasn’t directly linked to marital satisfaction, wives of snorers were nearly three times more likely to sleep separately compared to wives of non-snorers.18

Untreated OSA significantly impacts partners’ quality of life.11,19 General health-related quality of life scores were notably lower in partners of untreated OSA patients compared to the general population.11 Similarly, Doherty et al. observed lower quality of life scores in partners before CPAP treatment began compared to age- and sex-matched norms, indicating impaired quality of life, with over 50% reporting anxiety and 18% depressive symptoms.19 However, some studies found no significant difference in pretreatment quality of life between partners and national norms, except in specific areas like bodily pain.20,21 It’s important to note that these studies primarily involved partners who shared a bed. Interestingly, partners who did not share a bed with an OSA patient reported even worse quality of life and higher depression and anxiety than those who did share a bed.19

Interviews with spouses revealed that managing life with an untreated OSA patient often involves personal sacrifices, such as reducing social activities and taking on more household duties due to the patient’s fatigue.22 This imbalance frequently leads to relationship problems and a shift in spousal roles towards caregiver. Partners also described taking control by ensuring the patient sought treatment and by maintaining bed sharing to monitor breathing, which further blurred spousal roles into parental ones. Dietary and lifestyle changes were often adopted by both partners as a coping mechanism, with spouses providing support and actively participating in these changes. Finally, empathy and adaptation were key strategies, with partners adjusting daily activities to accommodate the patient’s tiredness and trying to make the best of the situation.

Positive Effects of OSA Treatments on Partners

CPAP Therapy

CPAP treatment for OSA generally has positive effects on partners‘ physical and mental health, with improvements observed both immediately and sustained over time (Table 2). Immediate improvements in PSG-measured sleep efficiency and REM sleep, along with decreases in arousals, were seen in partners when patients used CPAP during diagnostic sleep studies.14 A crossover study of CPAP vs. placebo showed partners of CPAP-treated patients reported better sleep quality and less disturbance after one month compared to placebo, although some reported sleep disturbance from CPAP-related noise or air leaks.11 In contrast, another study found significant improvements in sleep quality, daytime alertness, mood, quality of life, and relationship quality in partners of men with moderate-severe OSA randomized to CPAP, compared to sham CPAP, at a 4-week follow-up, with these benefits lasting up to 12 months.23,24 Partners of patients treated with CPAP for 6 weeks showed reduced daytime sleepiness, anxiety, and improved quality of life in several SF-36 domains.19 Similarly, another study found significant improvements in daytime sleepiness, overall quality of life, and specific SF-36 domains after 6 weeks of CPAP.21 Furthermore, after 12 weeks of CPAP, female partners of men with OSA reported significant improvements in their own depression symptoms and sexual function across all domains of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI).25 Focus group discussions revealed that while the initial silence from snoring cessation with CPAP could be alarming, partners quickly adapted and reported faster sleep onset, increased energy, improved mood, and resumed bed sharing.13

Table 2. Effects of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treatment on Partner-Assessed Outcomes.

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t02.jpg

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t02.jpg

Studies on CPAP’s effect on marital satisfaction show mixed results. A prospective trial comparing CPAP to conservative treatment found that partners of CPAP-treated patients reported greater improvements in marital satisfaction and fewer disagreements after 3 months, although bed-sharing frequency remained unchanged.26 However, another study found no significant improvements in partners’ relationship quality, daytime sleepiness, depression, or functional impairment with CPAP treatment, possibly due to already normal baseline levels, creating a floor effect.27

Oral Appliances

A study on oral appliances (OA) found that partners of patients who continued OA use after a median of 7 months reported greater sleep quality improvements than partners of those who discontinued use.28 Increased bed sharing was noted among OA users’ partners, but marital satisfaction remained unchanged. Another study reported that 64% of partners noticed improved sleep after 3 months of OA treatment.29

Among partners of patients using OA, over half reported improvements in general well-being, mental energy, sleep quality, and reduced daytime sleepiness after one year.30 A comparative study of two OAs found that a high percentage of partners (94%) reported better sleep quality, quality of life, and relationship quality at 3-month follow-up, with these improvements sustained up to 4.5 years.31,32

However, a short-term crossover study of OA vs. control device found no quality of life improvements in partners, possibly due to the brief study duration.33

Surgery

Research on radiofrequency tissue ablation (RFTA) surgery for snoring and OSA showed that partners of OSA patients treated with RFTA experienced significant reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms, while partners of simple snorers did not show reduced anxiety. Daytime sleepiness remained unchanged for both groups.34

Partner Involvement in OSA Treatment Adherence

Impact of Having a Spouse or Live-In Partner

Limited evidence suggests that having a spouse or live-in partner, and the frequency of bed sharing, can influence a patient’s acceptance and adherence to OSA treatment (Table 3). Living with a partner was linked to CPAP acceptance for higher-income patients, but not for low-income patients.35 Newly diagnosed OSA patients living alone used CPAP significantly less in the first month compared to those living with a partner (3.6 vs. 5.0 hours/night).36 Another study found that married individuals or those living with a partner were 1.5 times more likely to adhere to CPAP (≥4 hours/night) over an average of 504 days.37 Conversely, a study of older men found no difference in spousal presence between CPAP-adherent and non-adherent groups.38 Interestingly, having a partner who sleeps in a separate room quadrupled the odds of purchasing a CPAP machine, possibly indicating a stronger motivation to address the snoring issue.39 Bed sharing frequency was also linked to CPAP adherence, with more nights spent together associated with higher CPAP usage in the initial weeks of treatment.40 Increased bed sharing reported by partners post-OA initiation was associated with continued OA use, and lower pre-OA marital satisfaction reported by the partner also correlated with continued OA use.28

Table 3. Partner Involvement in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treatment.

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t03.jpg

graphic file with name jcsm.13.3.467.t03.jpg

The Role of Partner Involvement

Research on partner involvement in CPAP therapy adherence has primarily focused on patient-reported perspectives. Studies show that 38% to 53% of CPAP purchasers reported partner encouragement.39,41 Marital conflict, particularly negative emotions reported by the patient, was associated with lower CPAP adherence in the first 3 months, while patient-reported marital support was not significantly linked to adherence.27

A daily questionnaire study on spousal involvement (pressure, collaboration, support) during initial CPAP use found that most patients felt supported by their spouse to use CPAP. Perceived spousal support predicted increased next-day CPAP use, particularly in patients with higher OSA severity. Increased collaboration from spouses was noted following nights with decreased adherence. Low marital conflict was associated with greater collaboration after CPAP-related issues. Perceived pressure from spouses did not predict adherence.42 A detailed assessment of spousal involvement (collaborative, one-sided, positive, negative) revealed that both positive and negative involvement occurred early in treatment, with negative involvement decreasing over time. Collaborative spousal involvement was linked to greater 3-month CPAP adherence. One-sided, positive, and negative involvement types were not significantly associated with adherence.43

Qualitative studies have captured both patient and partner perspectives. Partner engagement in education during diagnosis and treatment, and practical support (mask adjustments), were seen as facilitators for CPAP adherence.44 Conversely, insufficient emotional and practical support was a barrier. Partners themselves identified emotional support (encouragement) and instrumental support (reminders, mask assistance) as motivators for patient CPAP use.13 Unmarried patients reported less support, less self-efficacy in CPAP use, and fewer positive CPAP experiences compared to married patients.45 Partners in another study described factors influencing their support, including CPAP sounds disrupting their sleep, patient physical/practical problems with CPAP, patient shame, interference with intimacy, and partner availability. Motivators for support included understanding OSA consequences, seeing treatment benefits, patient positivity, and support from others. Partners adopted varied management strategies: hands-off, shared management with mutual support, or taking over treatment management with supervision and directives. Patient perspectives suggest that a hands-off approach from partners may not be effective during CPAP initiation, highlighting the importance of emotional and practical support.44

CONCLUSIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

OSA is clearly not just an individual issue; it significantly impacts partners. Symptoms and treatments have far-reaching effects on partners‘ sleep and daytime functioning. Research increasingly recognizes OSA as a shared problem, with treatments benefiting both patients and their partners. Furthermore, partners play a crucial role, both positively and negatively, in patients’ OSA treatment journey. This review underscores the necessity of adopting a dyadic perspective in OSA diagnosis and management, considering both individuals in the partnership.

Recent studies link chronic illness symptoms in one partner to sleep and well-being impairments in the other.47–49 In OSA, snoring is a key factor in partners’ sleep disturbance, and partners also report disturbed sleep from monitoring patients’ breathing due to apneas. Long-term exposure to untreated OSA could potentially increase insomnia risk in bed partners, leading to dual sleep disorders within a couple. Longitudinal studies are needed to investigate this.

Population-based studies on couples show that both individual and partner sleep problems are associated with poorer physical and mental health, well-being, social engagement, and marital quality for both individuals.50 This suggests that the issues reported by partners of OSA patients—relationship problems, daytime sleepiness, anxiety, depression, and reduced quality of life—could stem from both their own and their partner’s sleep disruption. Partners also frequently resort to separate sleeping arrangements. Sex differences in co-sleeping couples’ sleep and the interplay between sleep and relationship dynamics have been noted in healthy couples.51–54 Women’s sleep can be disrupted by a male partner’s presence, while men’s subjective sleep may improve with a female partner present.54 Despite experiencing more objective sleep disturbances, women often prefer co-sleeping.52,53 In healthy couples, poorer sleep efficiency in men predicts negative partner perceptions the next day, while negative partner perceptions predict poorer sleep efficiency that night for women.51 Sex differences need consideration in future OSA and partner studies, but were not examined in the reviewed studies, which predominantly included female partners.

OSA treatments consistently improve partners’ sleep, but results vary for daytime sleepiness, quality of life, mood, and marital quality, possibly due to assessment variations and normal baseline levels. Generally, patient improvements are mirrored in partners, though patients often show greater improvement due to higher initial impairment. Future research should examine cross-partner effects of OSA treatments, considering that improvements in one partner likely influence the other. Treatment adherence is also crucial, as patient symptom improvement, and thus partner outcomes, depend on consistent treatment use. Notably, partner outcomes are scarcely assessed in surgical OSA treatment studies, raising the question of whether they should be standard outcome measures in OSA treatment trials, especially surgical ones.

Extensive literature shows partners’ influence on health behaviors, with positive involvement (encouragement, collaboration) enhancing patient engagement, while negative involvement (criticism) can be counterproductive.55–62 Partners influence all CPAP therapy phases, from initiation to long-term use. Partner prompting can initiate treatment seeking but may negatively affect long-term CPAP adherence if perceived as coercive.63 Partner approaches to CPAP initiation vary widely, impacting patient motivation. Collaborative and supportive partner involvement appears crucial for CPAP adherence.42–44 Partner involvement assessment has largely been patient-centric, with limited partner perspectives. Future research needs to consider the dyadic nature of partner involvement, measuring both patient and partner perspectives independently, as perceived and actual involvement may differ. Relationship quality, couple’s sex, and partner knowledge/attitude towards OSA and CPAP are also important factors in partner involvement and CPAP adherence.64

Meta-analyses of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illnesses show modest improvements in patient depression, marital function, and pain, as well as partner psychological and marital function.65 Addressing partner concerns, well-being, communication, and actions influencing patient health behaviors may enhance couple-oriented interventions.65 A couple-oriented CPAP adherence intervention is lacking. While some CPAP adherence studies included partners in sessions, they weren’t couple-based.63,66 Focus groups suggest partner inclusion in CPAP programs is vital, with partners expressing interest in learning about OSA consequences and CPAP benefits.13 Partner inclusion throughout OSA diagnosis and treatment could empower them to support patients. A collaborative approach to CPAP adherence interventions may be beneficial.42,43

This review highlights significant opportunities for future research to deepen our understanding of OSA and its treatments’ effects on partners, and partners’ roles in treatment adherence. Longitudinal studies with both patient and partner assessments will enable evaluation of interactive health outcome effects. Further insight into partner perspectives on their CPAP involvement and influencing factors can guide the development of couple-based CPAP adherence interventions. Clinicians should emphasize partner engagement in discussions about OSA’s negative health impacts and treatment benefits for both patients and their partners.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Support for Dr. Luyster was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) K23 HL105887. Dr. Luyster has indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

AHI apnea-hypopnea index

BMI body mass index

CPAP continuous positive airway pressure

FSFI Female Sexual Function Index

OA oral appliance

OSA obstructive sleep apnea

PSG polysomnography

REM rapid eye movement

RFTA radio-frequency tissue ablation

SAQLI Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index

SF-36 36-item Short Form Health Survey

REFERENCES

[1] Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. Burden of sleep apnea: rationale, design, and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. WMJ. 2009;108(5):246–249.

[2] Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–1053.

[3] Peker Y, Hedner J, Kraiczi H, Loth S. Reduced daytime vigilance in habitual snorers: a population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(6):1834–1840.

[4] Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):19–25.

[5] Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BH, White J, Wright J, Cullington J. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004410.

[6] Faccenda JF, Mackay TW, Boon NA, Douglas NJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):344–348.

[7] Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):173–178.

[8] Wolfson AR. Sleeping with a partner: sleep behavior and sleep quality in adult bed sharers vs. individual sleepers. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5(3):153–176.

[9] Janson C, Lindberg E, Gislason T, et al. Insomnia in men and women: a population-based study from three European countries. Sleep. 2001;24(2):167–175.

[10] Virkkula P, Polo O, Ermes M, et al. Partners of snorers: disturbed sleep and strain. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007;69(1):35–40.

[11] Bardwell WA, Loredo JS, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Effect of treatment of sleep apnea on супруги of patients: a randomized trial. Sleep. 2001;24(7):793–798.

[12] Cistulli PA, 회의론자 RJ, Bye PT. Sleep apnea syndrome: impact on супруги. Chest. 1995;108(6):1523–1528.

[13] Richards KC, Sternberg EM, Loeb R,灵적 RM. Partners’ perspectives on living with супруги who have obstructive sleep apnea. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(3):321–333.

[14] Hoffstein V, Mateika S. Snoring and sleep architecture in супруги of patients with sleep apnea. Sleep. 1992;15(4):351–355.

[15] Bakker JP, Kaemingk M, de Vries N, et al. Sleep architecture in bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a community-based study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(6):537–542.

[16] Salonen MK, Toivonen T, Partinen M, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep EEG and heart rate variability in супруги of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(1 Pt 2):153–162.

[17] Krieger J, Maglasiu D, Kurtz D. Marital status and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1989;12(3):275–280.

[18] Gislason T, Benediktsdottir B, Teiste J, et al. Snoring, sleep apnea, and супруги. Sleep Breath. 2000;4(2):69–77.

[19] Doherty LS, Kiely J, Swan V, et al. Impact of супруги of patients with obstructive sleep apnoea on quality of life, psychological morbidity and супруги’s quality of sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;14(2):227–232.

[20] Øverland B, Glozier N, Mørkrid K, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and their супруги. Sleep Med. 2011;12(2):157–161.

[21] Parish JM, Lyng C. Quality of life in bed супруги of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a preliminary investigation. J Clin Sleep Med. 2003;6(2):149–155.

[22] Eriksson M, Westman G, Stegmark-Andersson TV, Lindberg M. ‘It’s like living with a disabled person’ – супруги’s experiences of living with a partner with obstructive sleep apnoea. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(12):2652–2661.

[23] Alessi C,лецкий M, Richards KC, et al. Effects of treating obstructive sleep apnea in men on супруги’s psychological and marital functioning: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(8):878–885.

[24] Richards KC, Alessi C,лецкий M, et al. One-year follow-up of супруги’s psychological and marital functioning after treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in men. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(4):409–416.

[25] Budweiser S, Jörres RA, Heinemann F, et al. Effect of treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea on sexual function in women. Thorax. 2007;62(11):1002–1006.

[26] El-Solh AA, Bhattarai P, هاشو M, et al. Effect of treating obstructive sleep apnea on marital satisfaction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(5):411–416.

[27] Baron KG, Gunn HE, Wolfe L, et al. Marital conflict and CPAP adherence. Behav Sleep Med. 2012;10(1):51–62.

[28] Walker-Engström ML, Ringqvist I, 앱스타인 PE, Tegelberg A. A prospective study comparing two different mandibular advancement devices for the treatment of snoring and mild to moderate sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2003;7(3):117–130.

[29] Van Gestel JP, de Vries N, de Ru JA, et al. Oral appliance therapy for obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: a clinical evaluation. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98(5):344–351.

[30] Gindre J, Golmard JL, Pajot O, et al. Long-term effects of mandibular advancement devices on супруги’s quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med. 2013;14(1):83–88.

[31] Barnes M, McEvoy RD, Banks S, et al. Efficacy of three mandibular advancement devices for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized crossover trial. Sleep. 2004;27(4):631–642.

[32] Barnes M, Anderson C, Roeger L, et al. Long-term use of mandibular advancement devices for obstructive sleep apnea: impact on daytime function, sleepiness, and quality of life. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1719–1727.

[33] Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al. Oral appliances for snoring and mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2003;26(5):599–604.

[34] Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the tongue base: initial outcomes in obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):256–267.

[35] Weaver TE, Lewis MA, Naughton MT, et al. Factors associated with CPAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1995;18(1):1–6.

[36] Mehra R, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Predictors of adherence to CPAP therapy in older men with obstructive sleep apnea: the MrOS Sleep Study. Sleep. 2011;34(2):181–191.

[37] Gagnadoux F, Radu AS, Onen F, et al. CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea: influence of супруги. Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):942–946.

[38] Hofford JM, Kaplan J, Seiden JA, et al. Predictors of compliance with continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea in older males. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(7):701–704.

[39] Hoffstein V, Viner S, Mateika S, et al. Predictors of purchase of oral appliances for snoring and sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 1999;3(2):55–62.

[40] Cartwright RD. Effect of sleep position and bed супруги presence on sleep apnea severity. Sleep. 1984;7(2):110–113.

[41] Viner S, Szalai JP, Hoffstein V. Predictors of compliance with continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1 Pt 1):21–24.

[42] Bartholomew LK, Lee ER, Jago R, et al. Spousal support and adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep Med. 2008;9(4):408–413.

[43] Bengtson AC, Nettelbladt U, Lindberg E, et al. Spousal involvement during initiation of continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(4):1087–1095.

[44] Broström A, Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a qualitative study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):601–607.

[45] Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Tessier S, et al. Unmarried patients with obstructive sleep apnea are less likely to be adherent with continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(1):359–365.

[46] Elfström ML, Bengtson AC, Lindberg E, et al. Situations influencing супруги’s support to patients with obstructive sleep apnea during initiation of continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a qualitative study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(1):25–33.

[47] Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF III, et al. Sleep disturbance in bereaved spouses. JAMA. 1995;274(13):1036–1041.

[48] Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, et al. Sleep disturbance and psychological distress: evidence for reciprocal relations in older супруги. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):754–762.

[49] Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(2):260–300.

[50] de Jong JC, van den Berg JF, et al. Bidirectional associations between sleep problems and health-related quality of life in couples. Sleep. 2015;38(7):1079–1087.

[51] Prather AA, Epel ES, Puterman E, et al. Sleep quality and супруги’s perceptions of relationship interactions: within-couple daily assessment. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):91–94.

[52] Monroe LJ. Psychological and physiological differences between good and poor sleepers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1967;72(3):255–264.

[53] Merlino IM, Bernhofer EI, Wyatt JK, et al. Bedtime social contact and sleep in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(1):85–91.

[54] Showalter BA, Sammel MD, et al. Sex differences in sleep and супруги relationships in healthy older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(3):S127–S134.

[55] Burman B, Margolin G. Patterns of adjustment in супруги of chronically ill patients: are супруги distressed by the same stressors? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(5):725–733.

[56] Dakof GA, Lewis MA. The impact of супруги on treatment outcomes of drug abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1990;7(2):61–69.

[57] Fekete EM, Stephens MA, Mickelson KD. Spousal influence on adherence to medical recommendations: the role of spousal communication. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):104–111.

[58] Martire LM, Lustig A, Schulz R, et al. Social support and adjustment to cancer: processes and pathways. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(1):142–156.

[59] Pistrang N, Barker C, Humphreys K. Mutual help groups for mental health problems: a review of the effectiveness literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):514–522.

[60] Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Butler EA, et al. Emotion, verbal behavior, and marital interaction: does congruent negativity promote or inhibit problem solving? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(5):787–797.

[61] Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–2219.

[62] Stephens MA, Franks MM, Townsend AL. Stress and rewards in супруги’ and daughters’ roles as caregivers for parents with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontologist. 1994;34(4):441–448.

[63] Borel AL, Pépin JL, Léger P, et al. Long-term compliance with CPAP therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(23):3014–3021.

[64] Weaver TE, Naughton MT, Sawyer AM, et al. Spousal influence on CPAP therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(2):621–627.

[65] Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, et al. Couple-oriented interventions for chronic illnesses: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):141–157.

[66] Hoy CJ, платформа CJ, Eastman CL. яркий light improves compliance in CPAP therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1306–1311.